James Family Archives

• Researching the Past

• Education for the Present

• Preservation for the Future

Last Will and Testament of David James (c. 1660-

Including an Accounting and Inventory of His Estate

On file with the James Family Archives

Below follows the complete and unabridged record of the Estate of David James

of Radnor Township, Chester County, Pennsylvania at the time of his death on June

27, 1739 including his Last Will and Testament, an accounting of his estate and the

record of his burial at the Great Valley Baptist Church in Devon, Pennsylvania. The

records identify his second wife Jane, children Isaac, Thomas, Sarah, Rebecca, Evan

and son-

____________________________________________________________________________________________________

From the Abstract of Wills and Administrations of Chester County, Pennsylvania

Volume 1 (1714-

David James, Radnor

March 10, 1737/8 July 2, 1739 F 117

Provides for wife Jane. To son Isaac 50/ etc. To son Thomas wearing apparel. To dau Sarah Thomas £10. To dau Rebecca Miles £10. To son Evan the Plantation where I live with Farming implements etc. £60 div at wife’s dec between daus Sarah, Rebecca & sons Thomas & Isaac. Gives 20/ towards walling the grave yard “where they shal bury me” & 20/ to David Thomas of Haverford “if he will dig my grave.” Ex son Evan James. Wits Griffith Lewellin – Maurice Lewellin, Jos John Lewellin. Test signed D.

____________________________________________________________________________________________________

Last Will & Testament of David James (1660-

Philadelphia County, Pennsylvania, Will Book F, Page 117

I DAVID JAMES of Radnor in the County of Chester and province of Pensylvania being infirm and sickly of body but of sound disposing memory Considering the uncertainty of this Life and that it is appointed for Men once to die and desirous to settle my temporal Estate in manner following first I will and desire that my Just debts and funerall Expences be paid and discharged by my Executor hereinafter named Then I give unto my well beloved Wife Jane James the bed and appurtenances and the use and benefit of the room we used to Sleep in the use and Liberty of the Cellar and her maintainance During her natural Life the one half of the Cow’s and Sheep a horse to ride on when She requires firewood brought to her hand and the Sum of Twendty pounds in money to be found and paid her by my Executor I also give her one Iron pot and a Case of Drawers and the Brass and Pewter I Leave to be divided between her and my two Daughters Sarah and Rebecca But in Case my said Wife shall be inclined to live in some other place and not with my Executor or that she should happen to marry then I give her as Afforsaid and the Sum of three pounds a year and one Cow the said three pounds to be paid yearly during her naturall Life and I do declare that what I have here Left her is to be in full Consideration of her thirds and Dower Then I give to my Son Isaac James one Shirt of my wearing Apparell and one Mare to be delivered to him Imediately after my decease and the Sum of fifty Shillings in money to be paid him at the decase of my Wife Then I give unto my Son Thomas the residue of my wearing Apparell (Except on pair of Shoes and a pair of Stockings and one Taners Shirt which I give to old William David) Then I give to my Daughter Sarah Thomas the Sum of ten pounds to be paid within three months next after my decease Then I give to my Daughter Rebecca Miles the Sum of ten pounds to be paid within three months next after my decease Then I give unto my Son Evan James the Plantation where I now live with the appurtenances thereto belonging to him his heirs and assignes forever And also all the Implements Husbandry and Household goods not already bequeathed AND further it is my Will that Sixty pounds of the money that I have at Interest be kept so during the Life time of my said Wife and in Case she cannot agree to be with my Executor then I intend three pounds of that Interest to be paid her as Is before mentioned in relation to her in my Will the which Sixty pounds after her decease I give and dispose as followeth that is to say Twenty pounds to my Daughter Sarah Twenty pounds to my Daughter Rebecca Seaventeen pounds ten shillings to my Son Thomas and Two pounds ten shillings to my Son Isaac, Then I give twenty shillings towards walling the grave yard where they shall bury me and Twenty Shillings to David Thomas of Haverford if he will dig my grave or to such person as shall perform that Service Then I give to my Son Evan James my big brass pan Lastly I nominate Constitute and appoint my said Son Evan James to be the Sole Executor of this my Last will and Testament and my Sons Thomas James and John Miles and friends Evan David and Griffith Lewellin to be my trustees to see this my last will and Testament faithfully Executed and I do hereby revoke all former Wills by me while ratifying and Confirming this to be my last will and testament In Witness whereof I have hereunto sett my hand and seall this tenth day of March in the year of our Lord one thousand seaven hundred and thirty Eight 1737/8.

David (“D” his Mark) James (S.S.)

Signed Sealed published and declared by the said David James to be his Last Will and Testament in the presence of

G. Lewellin

Mau Lewellin

Jos John Lewellin.

PHILADELPHIA July 8, 1739 Then personally appeard Griffith Lewellyn and Maurice Llewellyn two of the witnesses to the foregoing will and on their solemn Affirmation according to Law did declare they saw and heard David James the Testator Herein named Sign Seal publish and Declare the same Will to be his Last Will and Testament and that at the doing thereof he was of Sound mind memory and understanding to the best of their knowledge,

[Coran] Set: Evans Res: Gent.

BE IT REMEMBRED That on the second day of July 1739 The last Will and Testament of David James Deceased was proved in due form of Law and Probate and Letters Testamentary were granted to Evan James Sole Executor therein named being first solemnly Sworn according to Law well and truly to Administer the said Deceased Estate and to bring a true and perfect Inventory thereof into the Register Generals Office at Philadelphia at or before the second day of August next and a true and just Account when thereunto Lawfully required Given under the Seal of the said Office C.

Set: Evans Res: Gent.

____________________________________________________________________________________________________

AN INVENTORY of the good and chattels, Rights and Credits of DAVID JAMES of Radnor in the County of Chester and as followeth:

Wearing apparel……………………………………………………. 5 – 0 – 0

Ready money………………………………………………………… 19– 0 – 0

Riding mare & saddle & bridle……………………………………… 6 – 0 – 0

Bed & appurtenances given to his wife……………………………. 6 – 0 – 0

Case of Drawers and oval table……………………………………. 3 – 0 – 0

Eight old chairs………………………………………………………. 0 –12– 0

Old chest and two old bases……………………………………….. 0 –10– 0

Two skeins of linen…………………………………………………… 2 – 0 – 0

Woolen Yarn………………………………………………………….. 0 –12– 0

Two Claffbeds & their appurtenances……………………………… 3 – 0 – 0

A parcole of Wheat…………………………………………………… 0 – 7 – 6

Linen yarn……………………………………………………………… 0 – 6 – 0

A quantity of Dried meat……………………………………………… 0 – 5 – 0

Oats…………………………………………………………………… 1 – 0 – 0

Cross cut saw………………………………………………………… 0 – 5 – 0

Big wheel and two small ditto……………………………………… 0 – 10– 0

A parcole of logs……………………………………………………… 1 – 0 – 0

Wool and S W & Table……………………………………………… 0 –10– 0

Book, Welsh and English…………………………………………… 1 – 10– 0

Table Doughtrough and old salt case……………………………… 0 – 5 – 0

Four iron pots and baking iron……………………………………… 1 –10– 0

An iron fire shovel and tong, gridiron and pot hooks……………… 0 –15– 0

Four pewter dishes, plates and spoons…………………………… 0 – 5 – 0

Two pair of stileyards and hand bellows…………………………… 0 –12– 0

Butter and Cheese…………………………………………………… 1 – 0 – 0

A big brass pan……………………………………………………… 3 – 0 – 0

A parcole of Rye……………………………………………………… 1 – 5 – 0

A grindstone…………………………………………………………… 0 – 2 – 0

Four brass pans and Cheese press………………………………… 1 –10– 0

Cart and Appurtances………………………………………………… 50– 0 – 0

A plow and harrow and swingletrees and two pair of plow irons… 1 – 0 – 0

3 axes two grubbing hoes, iron claw……………………………… 1 – 0 – 0

Shovel and spade & 3 wooden hoes……………………………… 1 – 0 – 0

Hand saw, Adze two augurs and chiseles………………………… 0 – 5 – 0

A terse and 4 barrels………………………………………………… 0 – 5 – 0

80 sheep……………………………………………………………… 5 – 0 – 0

One syth and 5 sickles……………………………………………… 0 – 5 – 0

Little rings and 2 wedges…………………………………………… 0 – 2 – 0

5 cows………………………………………………………………… 12–10– 0

A bull and 4 yearling calves………………………………………… 5 – 0 – 0

3 calves………………………………………………………………… 1 – 0 – 0

Wheat & Rye in the ground………………………………………… 6 – 0 – 0

3 mares & horse & suckling colt…………………………………… 12– 0 – 0

Hay in the barn………………………………………………………… 1 – 0 – 0

2 pitchforks…………………………………………………………… 0 – 2 – 0

Chain and cutting knife……………………………………………… 0 – 2 – 0

Tub and 4 pails……………………………………………………… 0 – 2 – 0

James John bond for………………………………………………… 10– 0 – 0

Roger Davis and Rev. David Able for……………………………… 5 – 0 – 0

Evan David…………………………………………………………… 7 – 0 – 0

David John Taylor…………………………………………………… 5 – 0 – 0

Henry Harris a bond for……………………………………………… 10– 0 – 0

Morgan Evan and John Rowen a bond…………………………… 20– 0 – 0

John Roof and Philip David………………………………………… 20– 0 – 0

Thomas Loyd & John Perry bond for……………………………… 20– 0 – 0

Thomas & Evan Loyd bond for……………………………………… 50– 0 – 0

G. Lewellyn & Maurice Lewellyn…………………………………… 25– 0 – 0

James David and John Parry & Wm. Renenant…………………… 20– 0 – 0

James David bond for………………………………………………… 10– 0 – 0

David Roof hold for…………………………………………………… 5 – 0 – 0

Appraised this second day of July in the year of our Lord One thousand and seven hundred and thirty nine (July 2, 1739) by

Griffith John

G. Lewellyn

Thomas Loyd

Evan David

____________________________________________________________________________________________________

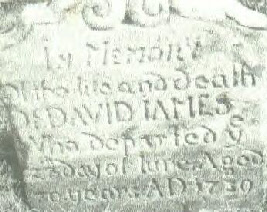

Records of the Great Valley Baptist Church, Transcribed 1896 By A.G.C.

Burials in Churchyard, Page 293

David James – died June 27, 1739 aged 70 years.*

____________________________________________________________________________________________________

Updated: September 20, 2025