James Family Archives

• Researching the Past

• Education for the Present

• Preservation for the Future

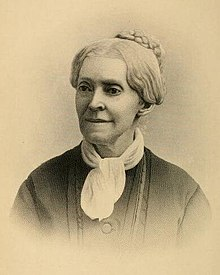

Biography of Mary Dagworthy (nee "Yard") James

(August 7, 1810 – October 4, 1883)

An American Hymn Writer

Mary Dagworthy (nee "Yard") James was born on August 7, 1810 in Trenton, New

Jersey to Benjamin Yard (1769-

Mary became a prominent figure in the Wesleyan Holiness Movement, assisting

Phoebe Palmer who is today considered the “Mother” of the Holiness Movement, and

often led meetings at Ocean Grove, New Jersey, and elsewhere. If Phoebe Palmer was

the Moses of the 19th-

About the same time, Phoebe was helping in a church in Burlington, New Jersey.

Mary had traveled about ten miles from her home in Mount Holly to be with Phoebe

and asked her to speak at a “female prayer-

The two women worked together in camp meetings also. In August 1848 they were at a camp meeting near Philadelphia. In a letter to Methodist Bishop and Mrs. Hamline, Phoebe wrote that “Sister James was present. How sweetly does her life exhibit the beauty of holiness. I think I never saw an individual more fully possessed of that love that thinketh no evil, than our beloved Sister James, yet as she professes the enjoyment of a state of holiness, she has her trials” (Wheatley, 79).

Phoebe was quite particular concerning who would lead the Tuesday Meeting in her absence. In April of 1845, Phoebe was confined to bed, and in a letter to Mary she explained her concern for the meeting and her contentment with the ability of her sister, Sarah, to lead the meeting. “You may wonder why I should regard it so needful, that a special person should be present to take charge of the meeting, when there are generally three or four ministers, and several leaders, etc., present. The reason is, as before stated, that it is a peculiar meeting, and needs that peculiar management, which very childlike—simple piety exhibits, and it is not every day that you can meet with those who know just how to come down to the simplicity of the gospel—but I think Sister Sarah does” (Wheatley, 246). Mary had the same skills, and Phoebe never hesitated to entrust the care of souls to her.

Mary’s personal ministry was varied. She started teaching Sunday school in the Methodist Episcopal Church when she was just 13 years of age. Her first class of young girls soon grew to include 12 “lambs.” Not content to see her girls just on Sundays, she would visit them in their homes, often taking gifts her mother had made. Mary continued her involvement in Sunday schools throughout her life, for she had a great love for children. She would lead children’s meetings at the Ocean Grove, New Jersey, camp meeting, and wrote a column for children in the Guide to Holiness.

Mary was one who made good use of music for spiritual goals. One evening, during a Methodist class meeting, a woman not known to the group sobbed through a confession that she had once been a child of God, but now lived with no hope. Mary felt the weight of the woman’s despair. As the woman finished speaking, Mary began to sing.

The feeble, the faithless, the weak are His care:

The helpless, the hopeless; He hears their sad prayer.

Through great tribulations His people He’ll bring,

And when they reach heaven the louder they’ll sing

(James, 137).

Mary’s great love, however, was the camp meeting. She attended her first camp meeting as a child, and was an advocate of meeting in the “forest temple” her whole life. A description of the “after meeting” at Penn’s Grove, New Jersey, in 1856 reveals her extensive involvement in evangelistic efforts.

The camp meeting had officially concluded on Saturday, but Mary and several others were staying on the campgrounds until Monday. During a prayer meeting on Saturday evening, the group realized that people from the surrounding area would probably come for services on Sunday. A few workers might be present with a “multitude of unconverted persons” gathering. Their prayer that evening was that God would multiply their “two loaves and a few small fishes.”

Mary was awake early Sunday morning and walked some distance from the camp to commune with God. “O there was a sanctity, a hollowed sweetness, in that blessed Sabbath day. As I lifted my heart to the Most High and asked Him to fill me with the Spirit, that I might be empowered to work for Him, I felt it descend upon me, and I was so strengthened with might in the inner man that I could not have hesitated to do any duty” (James, 286).

As she returned to the camp, she went to the cooking area where she talked with the cooks about Jesus. Only one out of six was a Christian. One promised to seek the Savior.

Mary asked God to guide her, and she found a woman who had been “blessed the night before” who needed some instruction in the life of faith.

At nine o’clock they started a testimony meeting. When Mary spoke, she spoke of her own experience, then preached an evangelistic message. Of the episode Mary wrote, “I was only the organ of clay through which God chose to speak to the people, but the power of the Spirit rested upon me. I felt it like fire in my bones” (James, 287).

A Universalist came to the campground that day in an argumentative spirit. After lunch a group formed around him. As Mary approached the group and listened for a bit, she told the man she wanted to ask him one question. He turned and left the camp grounds without hearing her question. Mary admonished the group on the truth of Christian doctrine, and led them in the song “We’re bound for the land of the pure and the holy, Will you go?” Several were converted in that impromptu meeting.

As Mary turned from this group, she saw several men sitting together, each looking quite somber. She was drawn to two brothers who, while presently sober, bore all of the signs of intemperance. Mary talked with them at great length, but both left the camp grounds without a spiritual breakthrough. One man returned that evening and was converted along with several others.

About midnight, just as someone suggested that it was time to close the meeting, a woman brought in a man who wanted to pray. The woman left and found another seeker, and the prayer meeting continued until about three o’clock Monday morning. The official camp meeting had ended on Saturday, but God was not finished, and Mary James and a few other workers were instruments of grace.

Mary not only served the Lord through personal encounters, but also through her writings. She was an avid letter writer and in 1853, Mary helped to found a home for orphans. Recipients of her letters included many young pastors. She believed that God had given her the responsibility to encourage and nurture those just beginning their ministries.

Her articles were published in many periodicals, including the Guide to Holiness, the New York Christian Advocate, The Contributor, The Christian Witness, The Christian Woman, The Christian Standard, and the Ocean Grove Record. Inspiration might come from a sermon, a snippet of a conversation, or something she read. Often she would wake in the night and ponder a newly discovered thought.

When she rose in the morning she would “scribble” the essence of her thoughts, then put them in final form at a later time (James, 240).

Sometimes her cogitations would result in a hymn. In her lifetime Mary had more than 50 hymns published. The tunes for Mary’s songs were written by several leading composers of the Wesleyan/Holiness Movement, including Phoebe Palmer Knapp, William Kirkpatrick, and John Sweney.

Mary’s most durable hymn was written as a New Year’s resolution. In her New Year’s letter for 1871, Mary reviewed the previous year. She rejoiced in her effectiveness for the cause of Christ. She wrote, “I have written more, talked more, prayed more, and thought more for Jesus than in any previous year, and had more peace of mind, resulting from a stronger and more simple faith in Him.” She recognized that her heightened ministry was a direct result of the depth of her commitment to God. She wrote “All for Jesus” as a commitment that in the coming year every action would reveal the glory and grace of God (James, 199). She also wrote The Soul Winner in 1883 before she died.

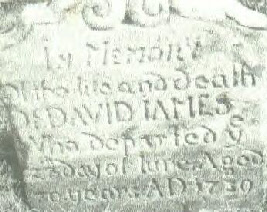

Mary Dagworthy James died on October 4, 1883 in New York City. Her prayer of commitment

was answered. A dozen years later, as her body was laid to rest in the Mercer Cemetery

at Trenton, New Jersey, inscribed on a granite monument was the simple statement:

“Her life was ALL FOR JESUS” (James, 360). Her children through Henry Boehm James

include: Joseph Henry James (1835-

Sources:

See, “ Mary Dagworthy James,” The Canterbury Dictionary of Hymnology.

See,:”Mary Dagworthy James,” Indelible Grace Hymn Book.

See, “Mary James,” The Center For Church Music, Songs and Hymns.