James Family Archives

• Researching the Past

• Education for the Present

• Preservation for the Future

Mat James and Children

By Dr. Jesse Clopton James (1924-

Written in 1982, Published by Scott Williams on Facebook in 2023

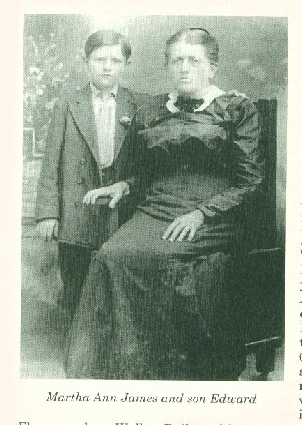

Below follows a biographical sketch of the life of Martha Ann Britnell James (1858-

Photo of Edward Newman James (1901-

Martha (“Mat”/”Mattie”) Ann Britnell James (1858-

____________________________________________________________________________________________________

[Page 1]

January 4, 1903, was a cold day in northwest Alabama. Two wagons drawn by two mules each made their way from the mountains of Rock Creek in Colbert County to East Florence in Lauderdale County. These wagons contained all the household goods and personal belongings of Mat James and eight children. They were leaving their home community of may years. One Wagon was driven by Arthur James, age 16, the oldest son of Mat. The other was driven by a friend of the family, probably George Sherill or one of the Henrys.

Mat was a recent widow of Andrew Jackson James. He died after a long illness on November

8 [1902]. Because of debts incurred during this illness Mat decided to sell the 160-

Mat's name before marriage was Martha Ann Britnell. She had been a school teacher at Belgreen before marriage just before her 27th birthday in June 1885. She had grown up in the South in Reconstruction days, not the most desirable life style. She lost her mother in 1900, her father in 1898, and two children since 1894. After selling the farm and paying all debts she had $400 in cash.

As Mat traveled to Florence that cold day in 1903 she probably didn't think about the misfortunes of her life because she was busy planning the future.

Mat and children spent the night of January 4 at the home of her youngest sister, Walker Daly, who lived in East Florence.

Within a few days they moved in to a rental house on Ashcraft Hill near Ashcraft Cotton Mill, and shortly afterwards all children 12 or older began working in the mill 12 hours per day for 25 cents per day. Cynthia began working at age ten; they didn't require a birth certificate.

The four oldest children worked at Ashcraft Cotton Mill to provide a family income of $1 per day. These four in older of age were Arthur, Myrtle, Eugene, and Cynthia. Willie and Lillie, twins, and Hugh entered grammar school. Edward was just 15 months old, so he remained at home with his mother who managed all family affairs. Mattie believed in education and preferred to have her children in school rather than...

[Page 2]

at work, but she had no choice. There were no welfare agencies, no social security, and in fact there was no financial help from anybody. Mattie had been the postmaster at Rock Creek and had been a school teacher, so she taught her children at home at night.

They attended church at Poplar Street Church of Christ which was quite a long walk from their house. They did not have good clothes to wear to church. They had no mode of transportation except walking. The four working children only walked a few blocks to work. Ther ghree grammar school children walked a reasonable distance to school.

The house at Ashcraft was located in an undesirable neighborhood. There were prostitutes, thieves, and drunks on the street. So Mat found a house to rent on Central Street between Aetna and Ironside Streets. It was the middle of three houses on the south side of Central near Aetna, about half way up East Hill.

They had a milk cow on Ashcraft Hill, but one day she was lying too near the tracks and the train cut off her legs.

The East Florence Church of Christ was established about this time so they only had two blocks to walk to church. They always attended church. A.J. James, their father, had been a faithful church member and an excellent Bible teacher at Rock Creek.

Two tragic things occurred on Central Street. Myrtle contracted typhoid fever and died. And the house burned. Most of their household goods burned with the house.

Myrtle was a very beautiful red-

Mat fed the family on garden vegetables and dried fruit pies. They had little meat.

They next lived with Ann Robinet on Minnehaha Street. This was very near Cherry Cotton

Mill. Later they moved to a three-

Edward can remember visits from George Sherill when they lived on Thompson Street. When somebody,

[Page 3]

Would knock on the door at that time they would yell, “Come in if your nose is clean; if not, crawl under”.

Andrew Jackson James owed George Sherill money when he died. Jack’s first wife had been a sister of George, but they had no children. George was in Co. E, Fourth Alabama Cavalry, during The War Between the States. Many other Franklin County and Rock Creek boys were in this fighting unit. These included Elias and Enoch James, Jack’s brothers. Richard and Killion Hill, John and Tom Pounders, James Quillen, J.W. And Pink Richard, Wash and Felix Srygley, Parham Sparks, John and Allen Taylor, Elburn Thorn, and J.M. Britnell.

General Joe Wheeler visited the Jameses in Rock Creek when he ran for office. He liked buttermilk.

Mat next moved the family down the hill to 333 Sweetwater Avenue. This was another

cotton mill house. Elmer and Elton Mills of Rock Creek moved to Mars Hill about this

time and they would occasionally visit the Jameses on Sweetwater Avenue. This house

was across the street from the cotton mill. In those days thee was a lot of activity

around the cotton mill. Loud whistles served as clocks for the people. Seetwater

Avenue had a lot of traffic, Mostly mule-

While living on Cherry Hill, Cynthia married Louis Coburn. Then Arthur married Donna Vessels. While at 333 Sweetwater Avenue Eugene married Peal Ray and Willie married Lee Watson. This left only two bread winners, Lillie and Hugh. Lillie worked at Cherry Mill but Hugh quit for a better job at Florence Wagon Works where Arthur was working.

Willie died May 21, 1915, while they were living on Sweetwater Avenue.

With just one family member working for Cherry Mill the manager frowned on the Jameses continued occupation of the company house. Also, Hugh had a long walk to work. So Mat found a good house on Trade Street. It was the nicest of all the places they had lived so far. It was two doors from Cole Street and had a good barn. It was on the west side of the street near where Garner’s store was later erected. John Hopkins lived in the corner house next to Cole Street.

At Trade Street they had a cow, hogs, and a garden. Edward had a pet pig which he fattened. Mat sold the pig.

[Page 4]

While living on Trade Street Willie’s son Edward Rudolph, lived with them for a short while. Later Rudolph died at the age of 2 yrs., 10 mo., and 3 days, on October 27, 1916.

Their next move was to 302 Industry Street. While living there Hugh married Meade Easley. By this time Edward began to work and contribute to the family income. Lillie was a steady breadwinner.

Mat purchased the house on Industry Street -

Times had bee hard for the Jameses since the death of their husband and father in 1902. When we reflect back on some of their misfortunes and hardships we wonder how they took it. People today buckle under hardships not nearly as severe. But the Jameses had one offsetting factor: They were close and helped each other and they believed in God. They lived in a community that was close. No wealthy people lived there. The Jameses became part of the East Florence community. They enjoyed simple things.

In the winter evenings they would gather around the fireplace or pot-

In the summertime they would sit on the front porch in chairs.

Mat paid $700 for the house on Industry Street. About the same time Louis Coburn paid $800 for his house about two blocks farther south on Industry Street. Edward’s wages at the Nitrate Plant made most of the house payments. Lillie’s wages at the cotton mill or knitting mill bought the groceries.

Edward began working at the Nitrate Plant during the winter of 1917. The bad flue epidemic came the next fall. Many people died. At the Nitrate Plant people would die at work. They wrapped the bodies, attached tags, piled them on trucks, and hauled them to the depot. One day two bodies fell off the truck along the road. The driver determined he was two short at the depot.

[Page 5]

Edward got the flue. When he returned to work all his carpenter crew had died.

The doctors were so busy, you couldn’t get one. Lillie and Edward were both sick at the same time. Edward was on a cot near the door and Lillie was on the bed. Mat flagged down the doctor as he was leaving a neighbor’s house, perhaps the Cole residence across the street.

Their principal mode of travel was walking. Edward rode a street car from East Florence to the Nitrate Plant for 5 cents. They never had an automobile. Never had an indoor toilet, and never had a telephone. Only a few people carried watches.

On Sunday mornings, Sunday nights, and Wednesday nights many church bells rang. The Catholic bell rang everyday at 6AM, Noon, and 6PM. Trains blew whistles. Many mills, factories, and shops blew whistles. On New Year’s eve night the sound, coupled with the firecrackers, was something to behold. The gas plant had a wildcat whistle which would startle a newcomer. The Cherry Cotton Mill had a whistle at 5AM, 6AM, Noon, 12:40PM, and 5:30PM. There were two toots when it was time to start work, but no warning before quitting time.

Mat lived at 302 Industry Street with Lillie and Edward until she died on September 29, 1925. At the time of her death Edward had married Ira Denton. They had one son named Clopton at the time Mat died.

Lillie never married. She finished the third grade then worked in cotton mills or

knitting mills the rest of her life until about age 70. At the end of the day her

hair would be white with cotton lint as she walked up East H ill. She bought me the

first bottled drink I ever had. This was in a small restaurant on the east bank of

Sweetwater Creek on Lee-

Aunt Lillie was a very kind-

[Page 6]

Body a gift. She always got Edward (and probably her other brothers) a white dress

shirt. All her friends, nieces, nephews, and inlaws received gifts. Lillie had several

unmarried (old-

On rare occasions an airplane would land at McFarland bottom near the river about a mile or two west of East Florence. Once Lillie went there an took an airplane ride with Reece and Evelyn Coburn. When up in the iar she prayed a fervent prayer to God and promised Him she would never get in another airplane, if He would get her down safely.

Aunt Lillie especially liked children, and urged them to be good. Once she had to see a dentist but she was scared. To help her feelings she took a bund of young kids with her (to sort of protect her). I’ll bet they were rewarded.

When Aunt Lillie was dying with cancer she never cried nor complained. I asked her

what she would most like to have to eat. She said, “A fried fruit pie”. At this time

she was living in a neat little house on Cole Street. She had to move from 302 Industry

becuae Brandon School purchased the land and house for a school-

Edward lived with Lillie on Industry Street until about 1930. Then he moved his family across the street to 1721 Central Street, and Hugh and his family moved in with Lillie.

During the 1930’s East Florence was in a depression and people didn’t have much. But they had more concern for each other than people do now in 1982. They respected their country, the elderly, and God much more than people do now. In a spiritual and emotional sense they enjoyed life more. People were concerned with rearing children and making a living. People helped each other and visited each other more. Lillie would walk to a friend’s house almost every night. Kids would build bon fires, often an old tire, in the middle of the street. That’s how little traffic there was. Aunt Lillie liked to come to our bon fires.

People walked everywhere. The street car line went out of business because people couldn’t afford the 5 cents fare.

[Page 7]

People on East Hill walked to buy groceries at Ramsey’s store west of the creek, the store next to Ramsey’s, at Matthew’s store at the corner of Lee Highway and Minnehaha, the store across Lee Highway from Matthews, or Grimes store on the top of Furnace Hill. Vegetables, chicken, and pork were usually grown at home. Light bread was not popular until the late 30’s. Most families had a milk cow. Refrigerators came along in the late 30’s. Radios and washing machines came along about the same time.

Mr. Fred Mitchell had one of the first radios. We went to his house to hear speeches by President Roosevelt or to hear a Joe Louis prize fight.

Edward made $12 per week at the International Agricultural Corporation. This was more than anybody else on the street made. Edward’s brothers said they worked so he could get an education. He lacked on or two years finishing high school.

[End]

____________________________________________________________________________________________________

About the Author

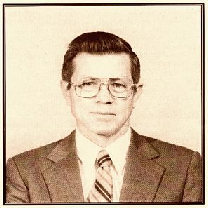

Dr. Jesse Clopton James (1924-

Dr. James grew up in the East Florence community of Sweetwater, Alabama where in

high school he worked at the local fertilizer plant for 15 cents an hour. He recalled,

however, that the hardest work he ever did was in his mother’s large garden where

he also fed the hogs, milked the cow, and on Saturdays drew water by hand out of

the 104-

Jesse, or Clopton as his family called him, graduated from Florence’s Coffee High School in 1941. He served in the Army Air Corps at the onset of WWII. While training to be a fighter pilot, he developed a serious illness, was hospitalized for months, and was honorably discharged. Jesse attended Auburn University, earning BS degrees in electrical engineering in 1945 and in engineering physics in 1946.

On September 27, 1947, Jesse Clopton married the love of his life, Barbara Brown Hayman in Jemison, Alabama. Together they were blessed with four children: Jeb Stuart, Jerry Hayman, Emily Caroline, and Barbara Kate. Jesse received his MA degree in nuclear physics in 1950 from Rice University and a PhD in electrical engineering and physics in 1958 at Georgia Tech. During these years, he worked for Southern Research Institute in many areas of analysis, design, and experimental fieldwork, as well as for the US Navy and Army.

Following graduation from Georgia Tech, he moved the family to Lexington, Massachusetts

to join MIT’s Lincoln Laboratory. In 1961, MIT moved the James family to El Campo,

Texas, where for nine years Jesse’s research group did ground breaking study of Venus,

Mars and the sun. In the 1960’s, he was the first to discover liquid water below

the surface of Mars using radio waves. In 1970, MIT sent the James family to Kwajalein

in the Marshall Islands where Jesse helped develop the government’s anti-

While on Kwajalein, he became an accomplished scuba diver and sailor, once sailing solo hundreds of miles across open ocean in a small boat to visit isolated islands. Following years in the development of our nation’s defense with MIT, McDonnell Douglas, and Teldyne Brown Engineering, he managed the Harvard Radio Astronomy Station near Fort Davis, Texas. Jesse wrote many chapters for technical books and authored 22 papers in scientific journals. He holds 12 patents plus another invention involving a stealth technique for planes and missiles for which a patent cannot be issued due to security classification.

Dr. James finally retired at the age of 82, but continued to work at tree farming

and woodworking, with (many family and friends enjoying fine furniture pieces lovingly

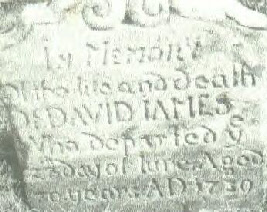

created by him). He did extensive family tree research before the age of the I\Internet,

visiting countless courthouse records and graveyards to write many volumes on the

family tree. At 92, he authored and published ‘The Bible: Two Proofs and Two Mis-

____________________________________________________________________________________________________

Updated: January 19, 2026